ANALYSIS: How Atlanta Displaces Black Families for Short-Term Projects

Aerial photographs courtesy of Georgia State University Library Blog.

(APN) ATLANTA — In the 1960s, the City of Atlanta, through legal and political maneuvers, displaced thousands of Black families in the former neighborhood Buttermilk Bottoms to create the Civic Center, which, only fifty years later, is now itself the subject of possible demolition.

Also in the 1960s, the City of Atlanta decimated parts of majority Black and mixed-race neighborhoods in Mechanicsville, Peoplestown, and Summerville, for the creation of the original Braves stadium, followed by Turner Field.

Last year, the Atlanta Braves announced they will be leaving Turner Field, and Atlanta altogether; and moving to Cobb County, meaning the likely end to the stadium complex itself.

What this pattern reveals is one of Atlanta’s most negative traits: the idea that nothing is sacred – not neighborhoods, not history, not the housing needs of low-income residents, and sometimes, not even the development projects that are used to justify the destruction of neighborhoods in the first place.

CIVIC CENTER

Where the Boisfeuillet Jones Civic Center now stands, there was once a neighborhood called Buttermilk Bottoms, housing thousands of Black families who were uprooted to make way for this monolithic, under-utilized venue.

“Buttermilk Bottoms was the most distressed neighborhood in Atlanta back then [in the 1950’s]. Some homes had no electricity and most did not have indoor plumbing,” Joyce Dorsey, Executive Director of the Fulton Atlanta Community Action Authority, told Atlanta Progressive News.

These families had little to no assistance with relocating, according to the book, Race, Class, and Urban Expansion by Prof. Larry Keating of Georgia Tech.

Then Mayor Ivan Allen ignored federal mandates and city ordinances demanding that redevelopment and rebuilding of public housing take place, once the construction of the Civic Center was completed in 1965, Keating’s book states.

Announced this year, Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed and other powers that be are looking to demolish the Civic Center in order to make way for the construction of a Hollywood-type studio.

Mayor Reed touts that it will bring urban renewal and jobs: the same thing that Mayor Allen claimed almost fifty years ago.

This begs the question: how many more Black communities will be displaced in Atlanta to make way for large venues that only have a shelf life of about forty or fifty years?

Some cities treasure historic buildings. In Atlanta, anything older than thirty years is considered by developers and their local government puppets to be decrepit, dilapidated, and antiquated.

Atlanta has a long history of displacing black families, from Buckhead to Candler Park to South Atlanta. Large event venues, majority White subdivisions, novelty shopping centers, and poor excuses for parks all exist today because of this trend.

The Civic Center construction displaced over one thousand Black households.

One group that fought the Civic Center was called U.-RESCUE, which stood for “Urban Renewal Emergency: Stop, Consider, Understand, Evaluate.” Efforts by neighborhood groups to acquire decent affordable housing only delayed, but did not stop, the mass evictions.

In concession to activists, the powers that be promised a public housing community to be called U Rescue Villa, a senior high rise Cosby Spears, and some subsidized housing, all of which is in a neighborhood now known as Bedford Pines.

Bedford Pines provided only 218 of its 1,400 rental units as subsidized housing for low-income families. This was less than 16 percent of the houses that were destroyed in the razing of Buttermilk Bottoms, according to Keating’s book.

Fast forward forty years: U Rescue Villa was quietly destroyed in 2008, as part of the Atlanta Housing Authority’s demolition of ten public housing communities. Only Cosby Spears remains of the neighborhood’s public housing inventory.

And Bedford Pines itself is endangered, with efforts by people like Peggy Denby of Midtown Ponce Security Alliance; and Councilman Kwanza Hall (District 2), to “revitalize” the area.

So much for the promises made to U.-RESCUE back in the 1960s. Those promises were all quietly forgotten and then revoked upon.

“We didn’t put up a fight because we knew this move had to happen. Churches got involved to help families buy new homes. Even Mayor Allen would visit the churches, preaching his assistance. I remember families being offered a stipend of 600 dollars. Back then, that was a lot of money. You put that down on a home and your monthly payments were less than one hundred dollars a month. Depending on where you relocated determined what class you ended up in,” Dorsey told APN.

There were many families that ended up moving into the areas that are now East Atlanta and Kirkwood, while others struggled to adapt or even find public housing. Those who did not find or were not offered public housing were left to their own devices.

“Anytime the government tells you taxes won’t go up with development, they’re not telling the truth. Somebody got paid. Streets, parking, it’s going to change the whole environment. The Civic Center changed the whole thing,” Charlie Christian, a former resident of Summerhill, told APN.

Christian recalled the conditions of the neighborhoods and those who lived there pre- and post- Civic Center construction. “The more people that are moved into one place, the more problems you’re gonna have. Once those high rises went in, it changed everything,” he said.

TURNER FIELD AND THE ATLANTA-FULTON COUNTY STADIUM (AND THE FALCONS STADIUMS)

Atlanta built the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium in 1965 to attract a major sports team; and in 1966, the Milwaukee Braves relocated to Atlanta from Wisconsin.

Eventually, that stadium was demolished in 1997, and another stadium was built across the street to accommodate the Olympics. That stadium is now known as Turner Field, and it too is about to be demolished, so that the Braves can continue their ongoing migration – this time, to Cobb County, Georgia.

When the Atlanta/Fulton Stadium was built in 1965, the neighborhoods surrounding it were promised urban renewal made up of mixed used developments, according to Keating’s book.

“Those people in Summerhill were fooled,” Christian said.

The feasibility study of the new stadium was aimed at supporting its construction and encouraging a baseball team to move to Atlanta; urban renewal of the area did not enter into the conversation.

The residents of those surrounding neighborhoods–Mechanicsville, Peopletown, and Summerhill–were showered with promises that were never kept.

A neighborhood fund, funded by a portion of parking revenue at Turner Field, has been used to fund the three respective neighborhood associations, who have, in turn, used the funds to cover community events, services, and projects. However, the funding has not been enough to make a dent in the community’s infrastructure needs.

In Peoplestown, the neighborhood was 49 percent Black and 51 percent White pre-construction, according to Keating’s book.

By 1970, five years after the stadium was built, the majority of the Jewish merchant population had vacated Peoplestown, leaving a population of approximately 5,100, 89 percent of whom were Black.

Those 5,100 in Peoplestown and many thousands more in Summerville and Mechanicsville, were now at the mercy of the massive influx of cars trying to park in too few spaces needed to accommodate a sold-out stadium.

Property owners in the surrounding neighborhoods demolished or burned down their houses to make way for makeshift parking lots, charging drivers a fee for use, Keating’s book states.

This demolishing of houses ran two to three blocks deep in all directions, leaving a desolate reminder of the houses that once stood in those vibrant communities, the book states.

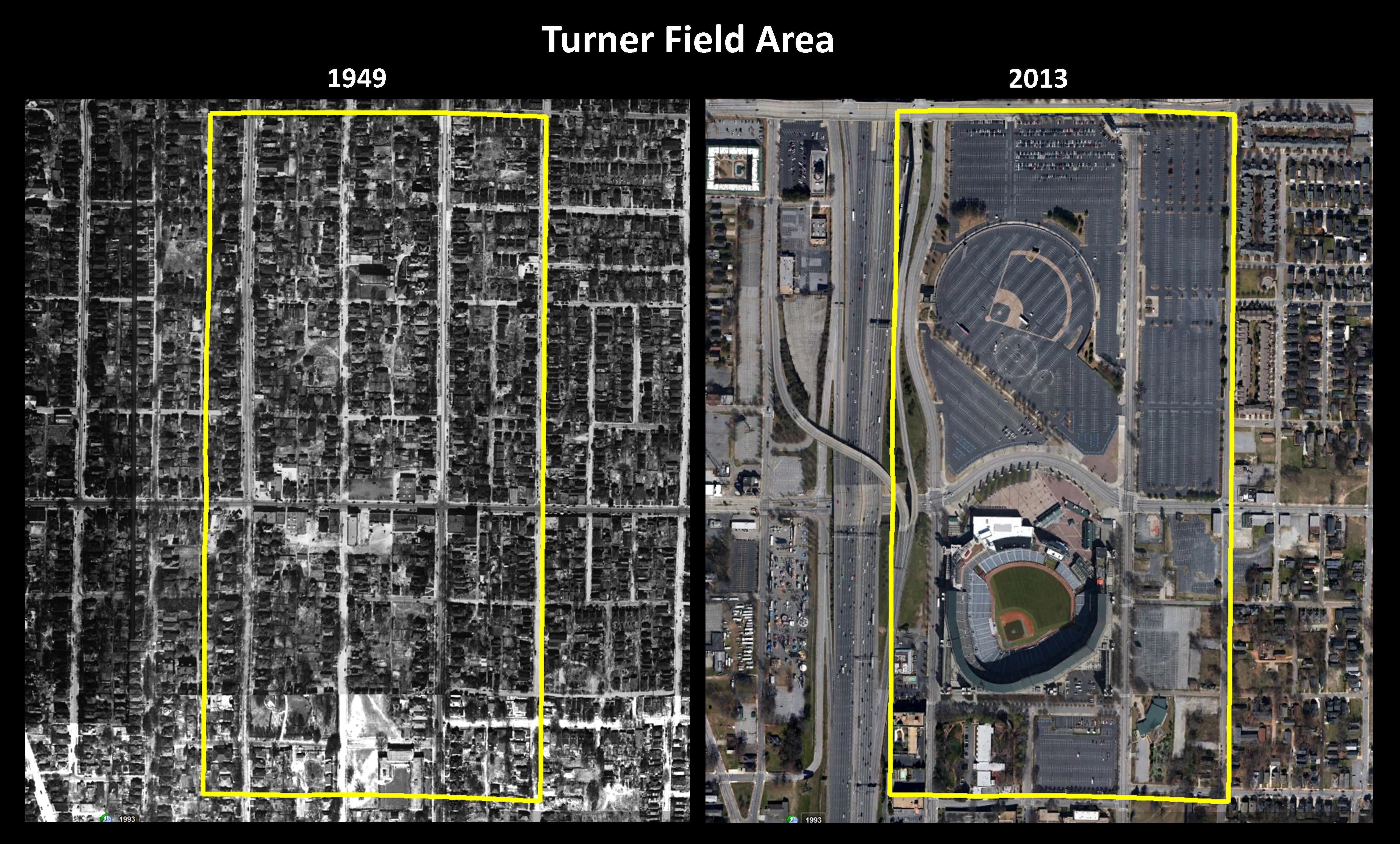

Georgia State University’s Library Blog posted an essay of maps and aerial photographs that starkly show the change in the Turner Field Area from 1949 to 2013:

For those who stayed, their streets were turned into one-way thoroughfares to allow the flow of traffic to and from the stadium. Homeowners were unable to leave their homes for a simple grocery store errand, as it was nearly impossible to get back without driving against traffic.

Also, as previously reported by APN, residents’ car insurance rates went up from being in close proximity to the stadium, where many car break-ins occur.

There were talks of a MARTA stop in the original agreements with the city and the Braves; that never happened.

The neighborhoods surrounding the stadium were left to suffer. Some of the worst crime rates in the city occur around the stadium. Housing values are upside down and the roads look like the surface of the moon, tore up and full of potholes the size of craters.

“The old neighborhood will never be the way it used to be. The old neighborhood will never be the same. The community and places of business,” Christian said.

Christian’s family was one of the many families that moved around from pocket to pocket as the City developed through low-income neighborhoods.

And now, in Atlanta’s Vine City neighborhood, two historic Black churches are being displaced so that the Atlanta Falcons football team can be accommodated with a new, taxpayer-subsidized stadium, just down the street from the current stadium. All this to prevent the Falcons from moving somewhere else.

With the advent of Civic Center, Turner Field and its predecessor, the Falcons Stadium, and even the freeway through Old Fourth Ward, neighborhoods including Buttermilk Bottoms and portions of Mechanicsville, Peoplestown, and Summerville have altogether suffered a loss of over 68,000 people, according to rough estimates by local planners, Keating’s book states.

Perhaps as many at 17,000 households did not find adequate housing after all the construction had ceased, the book states.

(END/2014)